The Land: Ancient Pontus

A massive line of mountains-the Pontic Alps of Turkey’s northern coast-sprang up along the line of impact, forming a natural wall that defines the southern rim of the sea.

The tectonic history accounts for several unusual features of the sea and the lands that surround it. The Black Sea is a geographical extension of the broad flatlands of eastern Europe, fully exposed on its smooth, gently sloping northern (Balkan and Russian) side, where the Danube, the Dnicpr and the Don bring in the waters of the enormously wide and wet east European basin. This excess of water creates a surface layer of very low salinity and a strong outflow through the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles-the narrow straits which connect the Black Sea with the Mediterranean. Underneath this thin upper layer flushed out through the straits, the antediluvian waters of the Black Sea lie undisturbed: they are saturated with the noxious gases produced by the disintegration of the flora of archaic times. and are so salty that few forms of life subsist in them below a depth of 200 meters (650 feet).

Above the surface, northerly and westerly winds predominate. They sweep over the sea, gathering moisture along the way until intercepted by the great natural barrier of the Pontic Mountains. That is where they deposit their load. The northern coast is bright and sunny; Odessa and Yalta are quasi-Mediterranean sea resorts. The south, by contrast, is more easily compared with the shores of America’s Pacific Northwest or southwestern Norway. The mountains are almost permanently cloudy and receive immense amounts of rain. Climate shapes the environment: nature runs amok; waterfalls and wild streams burst out of every clearing in the forest; fence poles take root and sprout leaves.

The Pontic Alps are young mountains, born at the same time as their European namesakes, with contours that have not yet settled into the placidity of geological middle age. They rise straight from the seabed at a depth of over 2000 meters to an average height of 3000 meters within a short distance inland. They increase in height and steepness in the east, where they press against the Caucasus Massif in the north. At the eastern edge, the permanently snow-capped peaks of the Tatos-Kaçkar Range soar to an altitude just short of 4000 meters. The “elbow” formed between them and the Caucasus enjoys the climate of a natural greenhouse. Temperatures are moderate, but vegetation takes on the character of a subtropical rain forest, with wild undergrowth, giant creepers and mossy beards hanging from majestic trees. Warm climate products like tea, citrus fruit and bananas grow in abundance.

This landscape is radically different from the sun-drenched maquis and arid steppe that one usually associates with the rest of Turkey. Except for the relatively low middle section around Samsun. the Pontic Alps rarely allow the humid winds to penetrate the Anatolian landmass and deliver the rain that would otherwise green the interior. This is most strikingly observed at any one of the eight road passes that cross the mountains east of Samsun at altitudes of 2000 to 2600 meters each. At the very top, the scenery changes abruptly from one of lush abundance into one more easily associated with the wastelands of Inner Asia. This sudden transition constitutes one of the most memorable images of any Black Sea Journey.

The transition also works in another way: just as the mountains block the humid winds of the north, so throughout the ages they have acted as a barrier against the historical currents that affected the lands to the south. While classical civilization flourished in the Mediterranean basin and great cultures rose and fell in the Anatolian interior, the Black Sea coast remained mostly untouched-an isolated and unique region with its own separate history and distinct amalgam of people.

At the Edge of Civilization

Ancient Greeks imagined the Black Sea as a distant, frightful and barbaric place the outer edge of the civilized world. They called it Pontos Auxenios, the Inhospitable Sea, before an early exercise in the art of public relations turned the name into Euxenios, the Truly Hospitable Sea.

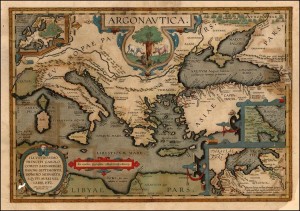

The ancient world’s earliest contact with the area goes back to sometime around 1000 BC. Its tale was told in the epic of Jason and the Argonauts. Jason, seething with rage at the usurpation of his father’s kingdom in Thessaly by an uncle, was persuaded to leave his homeland to seek the Golden Fleece in “cloud-bedecked Colchis” at the far end of the Black Sea where few ever went and even fewer returned. He set out aboard the Argo with a band of young rowdies, the heroes of a generation before the Trojan War. Bold, greedy and desperate, and like Columbus’ crew! outcasts for various reasons, they banded together to undertake the ultimate journey. They faced murderous moving rocks (the Symplegades, at the northern end of the Bosphorus), violent women (Amazons, inhabiting the land around the estuary of Yesihrmak, near today’s Terme), killer birds (at the Isle of Aretias, now Giresun Island) and an endless array of hostile tribes. Against all odds they succeeded in capturing the Golden Fleece, somewhere near today’s Hopa, by enlisting on their side the terrible passions of Medea, daughter of the king of Colchis.

In 400 BC an army of ten thousand mercenaries led by the Athenian Xenophon made its way through the Pontic mountains in retreat from the the Battle of Cunaxa.in Persia. In the Anabasis, Xenophon recalls fighting against no less than seven indigenous nations: the Taochi between Erzurum and Artvin, the Khaldi/Khalybes around Gumushane, the Scytheni further westward, the Macrones in the hinterland of

“Some boys belonging to the wealthy class of people had been specially fattened up by being fed on boiled chestnuts. Their flesh was soft and very pale, and they were practically as broad as they were tall. Front and back were colored brightly all over, tattooed with designs of flowers. They wanted to have sexual intercourse in public with the mistresses whom the Greeks brought with them, this being actually the normal thing in their country.”

HISTORY OF TRABZON AND PONTUS

but robbing and living on their plunder.” Similar sentiments were echoed eleven centuries later by the Turkish traveler Evliya Çelebi: “The people of the Trabzon region consist of Laz who are truly savage people, and exceedingly obstinate.”‘

Greeks and Natives

Gold came from the north, while copper was mined in the Pontic Mountains in the

Above and right: Not much has changed since the Mossynoeci 3rd millenium BC. It supplied most of Asia Minor during the Copper and Bronze Ages.

The Colchians were a branch of Georgians and spoke the same language before their dialect evolved into Laz/ Mingrelian.They set up a unified kingdom in the 6th century BC but more often lived in separate tribal units. Sadly, they left no written record of their achievements. The Khaldi, their western neighbors, mined iron and silver near modern Gumüshane (Argyropolis, or “Silvertown”),where rich silver ores continue to be exploited to the present day.

At the turn of the 1 st century BC :Vlithridates Eupator, the Hellenized Kim of Pontus, created an ephemeral empire stretching from Heracleia (Ereğlli) in the west to the Caucasus Mountains. Rulin~from Sinope, he battled the rising power of republican Rome for half a century before he was defeated by Pompey at Zeln (modern Zile, near Tokat). A final show of resistance by a follower was crushed on the same battlefield by ,Julius Caesar, who dismissed the event with the laconic epigram: vini vidi, vici.

Very few pre-Christian monuments survive from the Pontic cities. All we have is the bare knowledge that Cerasus had an acropolis where the Byzantine fortress how stands, that Trapezus had a fine temple of Mithra, or that a temple of Athena existed at Athinai (modern Pazar).

If there are few records from the Greek colonies, there are even fewer about the surrounding nations. We have only passing and inaccurate comments oh their subdivisions and customs. Except for Laz, a derivative of Georgian, little is known about the languages of the region. According to Strabo, the Tzani, who dominated the mountains between Trabzon and Giresun, spoke a related Caucasic language. The remaining dozen or so tongues are all together obscure, even though some survived until Ottoman times.

A big step in the direction of greater integration between natives and colonials came with Christianity. The Greek-speaking cities seem to have adopted Christianity in the 4th century along with the rest of the Roman Empire. The Laz and other tribes of the mountains embraced the Byzantine Church in the 6th, when the Laz King Tsatse converted. Thereafter they became, in Procopius’ words, “Christians of the most thoroughgoing kind”. They began to have closer contact with the Greeks and acquired various Hellenic cultural traits, including in some cases the language.

The interaction was hot always a comfortable one: Incensed by the high-handed behavior of Byzantine governors, Laz lords turned to the Persian Shah for help in 526 AD, precipitating a long round of wars between the two empires. During the early years of Justinian’s reign (527-565) generals Belisarius and Narses fought numerous battles in eastern Anatolia and along the Black Sea coast, erecting in the process an extraordinary chain of fortifications to defend the eastern marches of the Roman Empire. Many of these still survive and served as the model for all subsequent Byzantine (and Ottoman) military architecture. For the first five centuries of their existence they withstood countless raids by Persians from the east, Georgians from the north and Arabs from the south. They finally fell to the great conquering waves of the Turks.

Turks made their appearance on the Anatolian scene in the 11th century. In 1071 they destroyed the Byzantine army at Manzikert (Malazgirt, near Lake Van) and overran the interior plateau in one big sweep. The Black Sea coast was not affected by the conquest immediately, but the indirect effects were momentous. Soon Byzantine political authority began to disintegrate and autonomous fiefdoms under hereditary lords replaced imperial provinces. One of these lords, Alexis I Comnene, military ruler of western Black Sea, assumed the imperial crown in 1081. The old centralized administration of the Empire began to evolve towards Europeanstyle feudalism. Surprisingly, the results were not all that bad. Freed from the heavy hand of central government, the provinces actually began to flourish. There was an overall revival of trade, art, literature and religious and civil architecture. In the Black Sea area this trend culminated with the most fantastic and unusual episode of the region’s history: the Trebizond Empire of the Grand Comneni.

A Make-believe Empire: The Empire of Trebizond

Unfortunately, there were also other contenders for the lost throne: a Lascaris in Nicaea (Iznik), and another Comnene in Epirus (Albania). Their internecine fighting delayed the Byzantine recapture of Constantinople until 1261. Eventually it was the ruler of Nicaea who carried the prize, but by that time the self-styled Grand Comneni of Trebizond were too well entrenched to give up their claim to empire. After a while they consented to downgrade their title to a humbler “Basileus and Autocrator of All East, of Georgians, and of Lands Overseas”. They retained as their banner the single-headed Comnene eagle rather than the Byzantine double-headed eagle.

Surviving against all odds for two more centuries, they outlasted the fall of Byzantium in 1453 by eight years.

Two factors played a role in bringing about this unexpected resilience. One was trade. Trebizond had always been an important port for Asian caravans. But its hour of glory came after 1258 when the Mongol hordes of Genghis Khan captured Baghdad, devastating the old commercial centers of the eastern Mediterranean basin. Thereafter the great Silk Route was diverted northward. Persian, Chinese and Armenian merchants now carried the riches of Far Asia, through the Taklamakan Desert and 28

Khyber Pass, by way of Samarkand, Tabriz and Erzurum, to the port of Trebizond. From there Greek and Italian ships took the merchandise to Constantinople and points West. Located at the crossroads of world trade, Trebizond began to make more money than it knew how to spend.

The other factor was the great indigenous families of the region, the so-called mesokhaldaioi (“True Khaldians”) who basked in their new role as power brokers behind the imperial throne. These families had their strongholds in the countryside and probably descended from the original tribal aristocracies of the Pontic mountains. When they did not quarrel among themselves, they fought against the party of the scholarioi, the refugee courtiers who had arrived from Constantinople with the imperial family in 1204. Through a series of bloody civil wars (one of which totally destroyed the city in 1340) they succeeded in creating a delicate system of political balances where the emperor often functioned as no more than a figurehead.

Too rich and with too many vested interests involved, Trebizond could no longer return to the Byzantine fold. To maintain the legitimacy of its rulers it was obliged to keep up the pretense of an imperial Byzantine government-in-exile (echoes of Taiwan’?). A combination of wealth, astute diplomacy and the legendary beauty of Comnene princesses assured its survival vas-a-vas its warlike neighbors. For two centuries it shone as a brilliant city state on an alien horizon, a lone Christian Outpost in the Muslim Orient. It became a center of arts and learning. In the decadent style of its upper classes and the complexity of its faction-ridden politics it rivaled the contemporary Italian city-states of the early Renaissance. Pundits in Constantinople

sneered at the Laz Principality”. But when Constantinople had run out of funds to fix the leaking roof of its imperial palace, the imaginary Empire of Trebizond was still able to plate the domes of its churches with gold and to endow the most spectacular monasteries in Mt. Athos in Greece, having already built one in every gorge, cliff and mountaintop of its own territories.

The Genoese played an important role in the affairs of the empire. The Italian merchant state had aided the Byzantines it recapturing their capital from the Venetians and received in exchange a virtual monopoly on naval trade in the Orient, including the right to set up warehouses and colonies

on the Byzantine coastline. It soon exacted the same concessions from Trebizond. A walled Genoese colony was created facing the city at Leontoeastron (now Kale Park by the seashore) where representatives of some of the most illustrious Genoese families took residence: the Lercaris, delta Voltits, Ugolinos and Colornbos, who may have included the ancestors of Christopher, the future explorer. They controlled commerce, manipulated political factions and occasionally fought the Greeks on city streets. Identical privileges were granted in 1319 to the rival Venetians to balance out the overbearing power of the Genoese.

The two Italian powers ensured extensive cultural interaction with the west. The Venetian colony, for example, maintained a full-fledged orchestra of Italian musicians. A stream of European travelers came to admire the city, including the Venetian Marco Polo, the Englishman Geoffrey de Langley and the first great travel writer of the Spanish tradition, Ruy Gonzalez de Clavijo. Conversely, it was the Trebizondborn Cardinal Bessarion (1403-1472) who during his brilliant career at the court of the Medici first introduced Platonic philosophy and Greek scholarship to Renaissance Italy.

At the obverse of the western connection were equally intimate (and equally ambiguous) ties with the Empire’s Turkish neighbors. The Turks made a major effort in the 1220s to capture Trebizond but were eventually forced to settle for an annual tribute. In the chaotic period that followed the Mongol invasion of the 1250s, a variety of independent Turkish lords made raids into the Empire’s territory. They included the Beys of Sinop and Bayburt and the rulers of many other ephemeral states that succeeded each other in eastern Anatolia. A wave of semi-nomadic Turcomans, ancestors of today’s Cepnis, gradually penetrated the hinterlands of Giresun and actually held the second city of the Empire for a while.

But relations were by no means all hostile. A genuinely friendly alliance with the Muslim potentates seems to have existed between the Comneni and Timur (Tamerlane) who overran Persia and Anatolia at the turn of the 15th century, and the dynasty of the White Sheep who ruled Tabriz and Erzurum later that century. The Great feudal families of the Empire often preferred a Turkish alliance to one with the Italians, and occasionally even to one with their own Greek rulers. In 1311 Alexis II embarked on a joint naval expedition with the Bey of Sinop against Genoese colonies. In 1358 a leader of the Ünye Turcomans was officially recognized as an imperial vassal and married a daughter of Alexis 111.

In the complex web of the Empire’s diplomatic relations the hands of the pretty princesses of the Comnene house figured prominently. In the reign of Alexis III, it seems to have grown into a regular export business. A sister and five daughters of this monarch were presented for marriage to

various Turkish rulers. A sixth was sent to Constantinople to marry a son of Emperor John V Paleologue, but the old monarch, struck by her good looks, decided to take her instead. By degrees the beauty of the princesses of Trebizond acquired a quasilegendary status in the popular imagination, east and west. Travellers felt obliged to comment on it. Ambassadors reported on the prospects of imperial daughters. The ultimate case came with Despina Hatun, the pious daughter of John IV Comnene (1429-1458). She was married to Uzun Hasan, Bey of the White Sheep. After the fall of Trebizond her husband

tried, at her instigation, to galvanize European opinion against the victorious Ottomans. The effort failed but in the process the tale of the Christian lady held “captive” in partibus intideluum developed into a permanent fixture of European mythology, spawning an entire genre of 15th century popular romances. Among others they inspired Don Quixote to undertake his quest for Dulcinea.

The Sümela Monastery (Greek: Παναγία Σουμελά, Turkish: Sümela Manastırı) stands at the foot of a steep cliff facing the Altındere valley in the region of Maçka in Trabzon Province, Turkey. It is a major tourist attraction located in the Altındere National Park. It lies at an altitude of about 1200 metres overlooking much of the alpine scenery below. The monastery was founded in the year 386 (during the reign of the Emperor Theodosius I, AD 375 – 395) by two Athenian priests – Barnabas and Sophronius according to the Turkish Ministry of Culture. Legend states that they found an icon of the Virgin Mary in a cave on the mountain and decided to remain in order to establish the monastery.

Enter the Turks

systematically rebuild an eastern Empire. Mehmet 11, known as Fatih “the Conqueror”, knocked out decrepit Byzantium in 1453. In 1458 he took Amasra, the last Genoese holdout on the Black Sea. The same year saw the end of the Isfendiyaroklu, the Turkish dynasty of Sinop and Kastamonu. In 1461 a sweeping campaign along the Black Sea coast brought the Trebizond Empire to an end.

After a break of 400 years, the Pontic shores, along with the rest of Anatolia and the Balkans, were again integrated into a centralized administrative structure. Removed from the vortex of political rivalries the cities of the coast reverted to a marginal status within a larger unity. Until the 17th century they lived on as peaceful and prosperous, if uninteresting, provincial centers.

In keeping with Ottoman practice, twothirds of the Greek population of Trabzon were removed to other parts of the Empire at the time of the conquest. A majority were settled in Istanbul where they formed the core of the capital’s “Phanariote” families of Christian Greeks, exercising immense influence in the 17th and 18th centuries. They included the Ypsilantis,

whose descendants would eventually lead the Greek independence movement.

Few Turkish immigrants were brought into the newly conquered territories apart from Trabzon. The (Çepni tribesmen already formed an important element of the population of the Giresun highlands, but further east, the penetration of Turkish control proceeded very slowly. During the governorship of the future sultan Selim I in Trabzon (1490-1512) many highland clans came to terms for the first time with Ottoman rule. The Laz were converted to Islam; others followed suit after the collapse of Georgian power in the Caucasus during the

1540s. Yet others, like the Greek-speaking valleys dwellers of Of and Maçka, and possibly the highlanders of Hemşin came around in the 1680s. Some retained their ancestral dialects. Evliya Çelebi, traveling to Trabzon in 1641, reported at least three languages spoken there in addition to Turkish and Greek. Some who had earlier adopted Greek now learned Turkish, developing their own inimitably accented version of it. Still others retained the Greek language but became devout Muslims.

In direct continuation of the habits of the Trebizond Empire, the maintenance of law and order in remote areas was entrusted shortly after the conquest to dercbeyis, literally Lords of the Valley. Some of them were Turkish officers but most seem to have been local chieftains. In the Gümüshane-Torul region, Christian derebeyis still existed 150 years after the conquest. Initially these lords served as auxiliaries to the Pasa of Trabzon. When central authority began to wane in the I 8th century, they reappeared yet again as virtually independent petty sovereigns. The Haznedaroglus, Tuzcuoglus and Uzunoglus maintained their own troops, fought their own battles, and were not averse to some oldfashioned banditry or sea piracy in lean times. Their power was only broken at the cost of prolonged and bloody conflicts during the modernizing reign of Mahmut II (1808-1839). Some of their surviving seigneurial residences are among the highlights of a Black Sea tour.

Christian Greeks remained too. Concentrated in the coastal towns, notably Giresun where they formed a majority until sometime in the 19th century, as well as Tirebolu, Trabzon and Batumi, they kept to their age-old traditions of commerce and seafaring. The precipitous decline of commerce in the 17th century reduced their status and significance; its revival after the 1820s once again brought them into prominence. Wealthy Greek patricians of Trabzon, followed by those of Batumi, Samsun and Giresun, set up shipping firms, banks, insurance companies, churches, schools and magnificent private houses during the waning years of the Ottoman Empire. After a while some began to envisage a revived Pontic State centered in Trabzon. Russia played an important part in encouraging these aspirations. The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1776 recognized the Czar as the “protector” of the Orthodox Christian subjects of the Sultan, thereby opening up a sore that would fester for 150 years with ultimately tragic consequences. It allowed Russia and eventually other European powers to exploit the Christian “issue” to pry the Ottoman Empire apart. Under pressure the Sultan was forced to make concessions and grant special privileges to his Christian subjects. This in turn led to grave social imbalances and a growing perception that the Christian minorities constituted a menace to the Ottoman state.

The War of 1877 was the most traumatic of all. The heavy-handed treatment of Caucasian Muslims by Russia during it caused a massive wave of Muslim Circassians, Abkhazians, Georgians and Daghestanlis to seek refuge in Turkey. Many settled along the Black Sea coast, notably in Trabzon, Giresun and Ordu. Memories of 1877 in turn created a panicked flight of Muslim refugees before the Russian advance of 1916. During the occupation, local Greeks were accused of collaborating with the invaders. In the chaotic aftermath of the Russian withdrawal they formed armed units, in part to protect themselves against reprisals and in part to lay the groundwork for a Pontic Republic that many expected to ernerge from the melee. Muslims too, veterans of the bitter war of resistance against Russia in 1916, armed themselves in ad hoc militias to fight back. The Versailles Conference added to the confusion by awarding Trabzon as a seaport to the notional Armenian Republic that it presumed to create.

The Russian Revolution, followed by the Turkish Revolution which brought Mustafa Kemal to power in Ankara in 1920, sealed the outcome of the tug-of-war. Ankara was victorious in 1922 and in 1923 the Turkish Republic was declared. By the Treaty of Lausanne the same year all remaining Anatolian Greeks were expatriated in exchange for Turkish emigrants from Greece.

PEOPLE OF BLACK SEA REGION, TURKEY

First, the topography. Inaccessible valleys among trackless mountains constitutes the setting that has traditionally defined the Black Sea lifestyles. Like mountain people all over the world (one thinks specifically of the Scotsmen, the Basques or even the Swiss), their inhabitants have a highly developed sense of clan and community loyalties. They are intense and proud people, quick to respond to any perceived attack on their territory, honor or freedom-if necessary, by taking the law into their own hands. The manufacture and use of guns is a passion. The delimitation of highland meadows among villages and clans has traditionally given rise to serious hostilities that sometimes last for generations. But the same feeling of territory and honor also gives rise to an equally strong sense of hospitality. Any outsider who takes the trouble to visit these far-away valleys is automatically a guest and will be treated to the most cordial welcome. The open and friendly hospitality of the Turkish people is often cited as one of the main pleasures of traveling in Turkey. But the Black Sea region surpasses the rest of the country in this respect.

Second: The land may be wild but it is also prodigiously fertile. Unlike the interior highlands where culture has been shaped by centuries of grinding poverty, the Black Sea man tends to be merry, extroverted and colorful. People enjoy having fun to a degree that the more conservative parts of the country would consider scandalous. Their music is fast and boisterous, its lyrics often risque, its rhythms utterly unlike the melancholy strains of most Turkish music. Alcohol is consumed with gusto. Wit and a certain panache are appreciated, and eccentricity tolerated as a character trait. Telling tall tales is a regional specialty. These characteristics grow more accentuated as one moves eastward. At the eastern end one encounters an extraordinary quota of idiosyncratic individuals, with the unmistakable glint in the eyes and self-deprecating wit that are the Laz hallmarks.

The combination of intensity, wits and a good measure of clan solidarity seems to ensure business success. Spreading around the country, Black Sea people have earned a reputation (or notoriety) for gaining control of crucial businesses everywhere. Much of Turkey’s real estate and construction industry is owned by people from Trabzon and Rize. Most shipowners and seamen also come from there. The bread industry belongs to people from Of while (Çamlihemşin has a near-monopoly on pastryshops. The quirkiest financial genius of modern Turkey, thrice-bankrupted billionnaire Cevher Ozden, alias Kastelli, hails from Surmene. The country’s biggest export trader of recent years, Hasbi Menteşoglu, is an elementary school dropout from (Çarşamba. Politics is another field of prominence. Three major political parties have seen their Istanbul chapters led by men from Rize and (Çayeli in the last decade. A single village in Sürmene boasts two major politicians and two top public servants while Of has produced two party general secretaries.

Predictably the Black Sea man, or the “Laz” as he is called with a mixture of affection and sneer, has become a stock figure of the Turkish social typology, The stereotypical Laz is called either Temel or Dursun. He sports a majestic nose and speaks Turkish with an outrageous accent. His diet consists of hamsi (Black Sea

anchovies), cooked to the legendary one hundred recipes that include hamsi bread and hamsi jam, with corn bread and dark cabbage to accompany. He dances a wild horon to the syncopated, manic tunes of his kemençe.

His oddball sense of humor makes him the butt of an entire genre of jokes. To a certain extent these jokes correspond to those of the Polish, Scottish, Marsilian or Basque variety, but they lack the crude ridicule that characterizes some of the latter. In most stories Temel either pursues an altogether wacky idea, or responds to situations with an insane non-sequitur. The best ones contain a hint of self-mockery, and it is not really clear who the joke is on. Inevitably the most brilliant Laz jokes are invented and circulated by the Laz themselves.

Laz and Not-So-Laz Underneath these broad generalizations, the population of the Black Sea region forms in reality a crazy-quilt of different ethnic, linguistic and cultural units. The patchwork diversity of the Swiss or the indigenous cultures of the North American Pacific are the parallels that come to mind.

Take the Laz. For the average Turk any native of the Black Sea region is a “Laz”. But the average Turk who knows all about Temel and Dursun is often not aware that there exists a specific people called the Liz, who form only a small fraction of the people of the Black Sea. Numbering less than 150,000, the Laz in the proper sense of the term inhabit the five townships of Pazar, Ardeşen, Findikli, Arhavi and Hopa at the far eastern end of the Turkish coast as well as a few villages beyond the Soviet border. They have their own language, unrelated to Turkish, and their own history going back thousands of years. The Mingreli who live north of Batumi in the Soviet Union speak a version of the same language and differ mainly in that they remained Christians while the Laz converted to Islam some 500 years ago.

The Laz first surface in history when a kingdom bearing their name came to dominate Colchis through an obscure series of events in the I st century BC. The usual assumption is that they were originally a tribe or sub-unit of the Colchians. Romantics have speculated about a possible connection between the predominantly blond, blue-eyed Laz and the horde of Goths who devastated Trebizond in 276 AD and then dropped out of sight in this vicinity. No one has studied their language for Germanic traces. In its basic structure it is a linguistic relative of Georgian that is laced with a surfeit of borrowed Greek and Turkish words. It does not have a written form and, with the successful integration of the Laz into Turkish society, it is likely to disappear as a living language within a couple of generations.

Trabzon Traditional clothes in Ottoman empire era, man from Trabzon city, woman from Trabzon, man from rural area – Laz People

The inhabitants of the Trabzon and Rize countryside, too, are often given the blanket appellation of Laz, although they would never refer to themselves as such. The stereotypical “Laz” variety of Turkish is in fact a characteristic of this region. Despite a common accent and other unitying traits (notably female dress), this area presents a kaleidoscope of different cultures. The valleys of Of and (Çaykara, for example, speak a dialect of Greek as their first language and display a marked sense of distinct identity. They also boast the highest proportion of mosques, Quranic schools and bearded Muslim scholars in the whole country The valleys of Tonya and Maçka speak Greek, too. But they tend to take the precepts of Islam with a grain of salt and heap scorn on the pious antics of their linguistic relatives in Of. Both groups earnestly deny being at all of Greek descent-which may be partly an effect of Turkish Republican education, but more likely reflects a dim memory of the times when the Empire of Trebizond forcibly Hellenized the native tribes in these same mountains.

Turkish is the native language in other cantons of the Trabzon-Rite area. Little over 300 years ago though, the traveler Evliya (Çelebi reported that at least two more now extinct native languages were spoken in this area in addition to Turkish, Greek, Georgian and Laz. He recorded one specimen which seems heavily mixed with Greek but is otherwise unintelligible.

There is more to the collage. The district of Çamlihemsin in the Kaçkar highlands behind Pazar and Ardesen is inhabited by an altogether different people who are called the Hemsinlis. They display their own sense of communal identity, with their own music, traditional female dress and linguistic peculiarities. They are loath to he called Laz. Hemsinli communities settled further northeast in the mountain villages of Hopa speak a language called “Hemsince”, which turns out to be a dialect of Armenian.

The kemençe, a sort of piccolo violin with a tinny short-breathed sound perfectly suited to the neurotic accents of Black Sea music, is used in the Trabzon-Rite area and along the Laz coast east of Rize. The Hemsinlis and the villagers of the Artvin region, by contrast, play the tulum-a bagpipe made of goatskin producing a very Scottish-sounding drone. West of Giresun the customary Turkish zurna (a type of clarinette) and davul (kettledrum) take over the musical scene.

On the 68 kilometer drive between Hopa and Artvin, the traveler passes through four linguistic zones: Laz in Hopa. Hemhsinese in the mountains. Georgian in Borçka, and Turkish in Artvin-town. The Georgian-speakers of the Borçka-Camili and Meydancik valleys in Artvin province, located on opposite sides of the same mountain, employ mutually unintelligible dialects of the same language.

The Giresun highlands host a large number of (Çepni comnuinities who are descendants of the Türkmen tribes who settled here in the 13th century. They are said to adhere to the Alevi faith, a ” heretical” variety of Shiite Islam. When pressed for clarifications, though, they seem unable to explain the differences between their sect and mainstream Sunni Islam. Fatsa, Bolaman and their hinterland, by contrast, are more self-consciously Alevi and consequently embrace the left-wing political sympathies usually associated with that sect.

Giresun and Ordu also have large elements of immigrants from various parts of Turkey who moved in three generations ago to replace the departing Greeks. Trabzon city has a substantial community of Bosnian Muslims, immigrants from Yugoslavia. In the districts of Onye and Ordu many villages are populated by descendants of the Georgian and Abkhazian refugees of 1877, some of whom retain their old Ianguage.

Pontic Fashions

As in many other parts of Turkey, the most immediate manifestation of communal distinctions along the Black Sea coast is the traditional wear of women. Men are uniformly boring in their “western” garb.

Learning to recognize the telltale nuances of the colorful costumes of village women, on the other hand, can develop into one of the major joys of a Black Sea voyage. The beautiful hand-made fabrics that are used for these costumes make some of the most interesting souvenirs that one could bring back from a trip.

Traditional clothing is most commonly worn by women in the Trabzon-Rize area. The distinctive attire of this region consists of the pestemal, a boldly striped piece of linen wrapped around the waist, and the keşan, a finely patterned red-black-cream shawl that covers the head and torsosometimes the face as well when a stranger is seen to approach. The combination is worn in a precisely delimited region between Tirebolu in the west and Çayeli in the east. The keşan is more or less uniform within this region. Peştemal fashions, on the other hand, vary from district to district: burgundy/cream stripes are worn by all women in Akçaabat, brown/black dominates in Tonya, while most fashionconscious ladies prefer crimson/black in Sürmene. Rize has its own unique orange and prussian blue aprons. It is also interesting to note that in some highland districts the keşan-and-peştemal “look” was only adopted within the last generation. In Tonya and Maçka, for example, one can still see older women wearing a very different costume made of black silk brocade complemented with a bright orange waistcloth while younger women copy the “fashions” of the coast.

Both the Ordu-Giresun region in the west and the Laz districts east of Rize have mostly dropped traditional attires in favor of either the generalized Turkish peasant dress of loose print skirts or a modern appearance. Hemşinli women, by contrast, wear a wholly unique apparel which consists of patterned mountaineers’ socks, knee-length skirts made of black wool and bright orange silk scarves. These

scarves, interestingly enough, are not made locally but imported or smuggled in from the Middle East. They are wrapped in a special manner around the top of the head, over a black chiffon kerchief that is usually adorned with ornamental trinkets. The overall effect cannot fail to remind one of 13th century European fashions.

The transmontane interior is where one begins to encounter serious feminine cover-up. A black silk “chador” is in fashion in Gümüşhane and Torul. A white cotton towel often covers the mouth. In Bayburt, the visitor is treated to the striking sight of women clad from tip to toe in a

brown silk or wool “body bag” that completely covers their face as well.

The symbolic meaning that these traditional outfits carry for the wearer can he divined from the example of a lady seen at the Trabzon airport. Apparently the wife of a local politician and impeccably dressed in modern clothes, the young woman wore a spiffy European designer scarf with a plaid pattern in red, cream and black-the colors of a traditional keşan!

Town, Village, Yayla

Each canton has a main town that serves as administrative center and market. It is usually on the seashore, although the more interesting ones like amlıhemşin Maçka or Tonya are inland. The town is referred to as “the market”. Regarded as a merely functional public place, little attention is paid to its esthetic upkeep. In the pre-1923 order of things towns used to be primarily the domain of the Greeks. The prettiest ones today are where their legacy is most apparent, like Akçaabat and Tireholu. Since the departure of the Greeks, towns have been characterized by the unfortunate decay of architecturally valuable old neighborhoods and a property boom that has turned them into extended

construction sites. The boom is financed mostly by the remittances and savings of emigrants who have made good in the big city. Much of the money that they bring in is invested in real estate for long or very long term dividends-hence the endless rows of half finished apartment buildings that line the coast, and the countless brand new mosques that dot the landscape.

People may keep property and maintain ties in the town but the valley is where they usually have their ancestral home. Farmlands extend over the sharply rising terrain to an altitude of 1200 to 1500 meters. The most noticeable aspect of the landscape is that villages in the

Anatolian sense do not exist here. What is called a village is often a mosque, several cafes and sometimes a few shops, with bunches of farmhouses scattered all over the mountain and set apart by forest patches and fields.

Several reasons have been offered for this settlement pattern. One is that the danger of flooding compels people to build their houses on high and sloping ground (sometimes very high and very sloping indeed!). Another is that the abundance of water removes the need to huddle around a spring as in inner Anatolia. But perhaps the basic reason is the simplest one: these people like having a good view and detest it when their next-door neighbor looks down into their backyard. The cramped existence of the Anatolian peasant is something incomprehensible to the people of the Black Sea. Most folks cherish the idea of being the lord of one’s own valley, with the sense of freedom and self-respect that it engenders. It is in this setting that they feel safest, most confident and most hospitable.

It is also here that the best specimens of traditional Black Sea wood and woodland-stone architecture are to he found although they are fast giving way to apartment buildings that look utterly surreal standing in the middle of the wilderness. The building style of traditional houses varies between regions. The most gorgeous arc arguably in the district of Çamlıhemşin or in Artvin’s Meydancik valley. The Of and Sürmene uplands also offer fine examples, while the Torul-Kürtün area has its own unique style. Common features include being enormously panoramic, and often spacious enough to

accomodate an old-fashioned family of a dozen or two. A large family was once considered essential, as were a few well-drilled pistols, to deter a hostile approach-and old traditions die hard.

Situated above the village belt is the yayla country. Around 1200 meters, the landscape begins to change. Giant conifers replace deciduous trees while tea and hazelnut plantations disappear. Rhododendron ponticum, the yellow azalea and alpine lilies become ubiquitous. Vast rolling pastures, rising at every possible angle and curvature of the plane. extend to an altitude of 3000 meters. The sun shines more often here than in the cloudy low lands. Few people live in the yayla \ear round: in winter the re- ion is deserted sav -e for the solitary village fool, a few lost cows and a rare wilderness skier. Summer is a different story.

Above the Clouds

“Going up to the yayla” is the most exciting event of the year. Many people who have left the land of their birth to live elsewhere come back each year merely for the sake of the yayla. Many regard the yayla as a cleansing experience, attributing it an almost mystical aura. Some argue that one has not seen anything of the Black Sea if one hasn’t seen the yayla.

The yayla is dotted with summer settlements which tend to be older and more compact places than the villages lower down. Each is the property of a village or valley, with ancient imperial writs to back up the claim. The yayla season formally begins on the first day of summer, which ancient tradition places on the “Sixth of May” (May 20 on the modern calendar). The strangest millenial folk rituals are revived on this day. Everywhere people feast and make merry in the fields. Virgins bury a ring under a rose bush, evoking mysterious pre-Islamic (and pre-Christian) saints. Coarse grains are thrown into the wind to feed “the birds and the wolves”. At Giresun Island large crowds gather as they did in earliest Greek times, to throw 15 (“seven pairs and one”) pebbles into the water and to circle the island thrice in rowboats. Then, for three days they make music, dance the boron and soak themselves in alcohol.

The horon is usually performed by men. Dancers stand in a circle, holding hands. At first their steps are tentative, slow, even awkward. They gather speed as the music becomes wilder. The dance turns by degrees into the expression of an intense machismo, then increasingly into an explosive, boiling frenzy. The name of the dance is a legacy of the Greek choron and indicates a direct line of descent from the ancient Bacchic rites where celebrants went into a wild frenzy to honor the god of wine.

Merrymaking continues in the yayla, in fits and starts, throughout the season. The veneer of city culture gets stripped off. Oxcarts replace taxis while people who normally wear suit and tie put on their traditional dress. On appointed days, and often in between, they organize festivities. Guests from other valleys arrive on these days, along with the traveling bards, professional wrestlers, trinket sellers and the best dancers of the province. For three days and three nights, they drink, dance, wrestle, fight and gamble. Eternal friends and mortal enemies are made. Handguns and bagpipes come out of winter storage. Cows and bulls are decked out in festival frills. At Hidırnebi near Trabzon, participants form a 1000-person horon ring. At Kafkasor above Artvin, they hold bullfights. At Kadirga, at the intersection of the cantons of Maçka, Torul and Tonya, the three communities get together to reenact long-forgotten hostilities. Everyone is welcome at the festivities. Every visitor becomes part of the ongoing show.

And it is here in the breathtaking scenery of the mountains that the casual outsider first begins to penetrate the ,Wade, and catches a fleeting glimpse of the real spirit of the Black Sea.’